Game Protection

Intro

From time to time I take a closer look on protected games, to continue my series of Android this time its an Android game.

I dont know anything about law, and I dont want to get into trouble so I gonna

call the game LiveOfTurin and the library which would reveil the protection

will be called arkenstone.so during this summary.

Information Gathering

First things first, before staring IDA and frida and all the fancy tools, lets do some basic reconnaissance. apkpure is a great website to start. Cause while the latest game version might be protected, some older might be not.

Thats the case for this game, cause the older version does not have the

arkenstone.so library. Looking through the libraries:

libBlueDoveMediaRender.so

libil2cpp.so

libmain.so

libsqlite_unity_plugin.so

libunity.so

libxlua.so

The libil2cpp.so and libunity.so let us know that it is a game written with

the Unity Engine. To continue we can use il2cppdumper

to name functions in libil2cpp.so, this will help for later analysis with IDA.

For cross checking, we can also simply search the bytes of interesting functions

and check if they also exists in the libil2cpp.so of the current version. For

example in the old version we find the function:

// RVA: 0x381EF7C Offset: 0x381EF7C VA: 0x381EF7C

public long get_mydamage() { }

Checking it up in IDA we get the functions bytes:

.text:000000000381EF7C ; __int64 __fastcall get_mydamage_381EF7C(__int64)

.text:000000000381EF7C get_mydamage_381EF7C ; CODE XREF: sub_1686AE4+544↑p

.text:000000000381EF7C ; __unwind {

.text:000000000381EF7C 00 10 40 F9 LDR X0, [X0,#0x20]

.text:000000000381EF80 C0 03 5F D6 RET

.text:000000000381EF80 ; } // starts at 381EF7C

.text:000000000381EF80 ; End of function get_mydamage_381EF7C

Interestingly searching these bytes in the new libil2cpp.so shows no findings.

This already suspects that the file is probably encrypted, but at least we have

a function for which we can look for.

ELF inspection

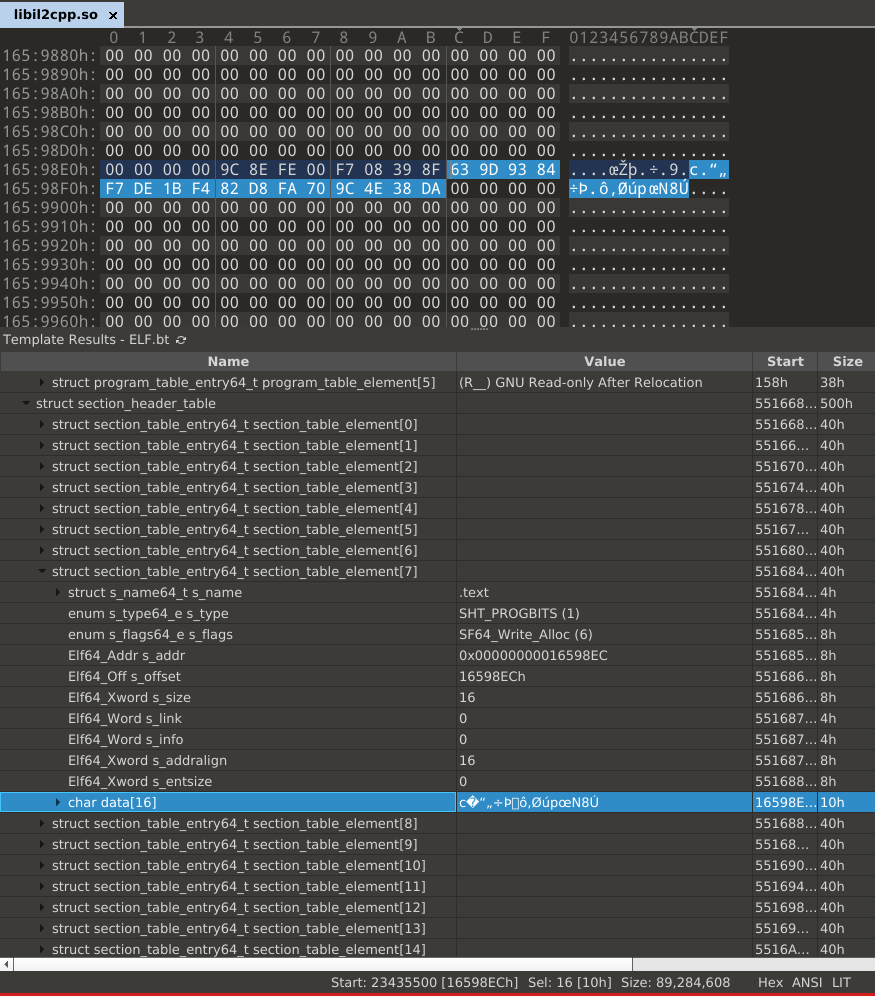

Not only did I not found any code, there is almost no code in the first place. Checking it with 010editor shows some pretty interesting stuff.

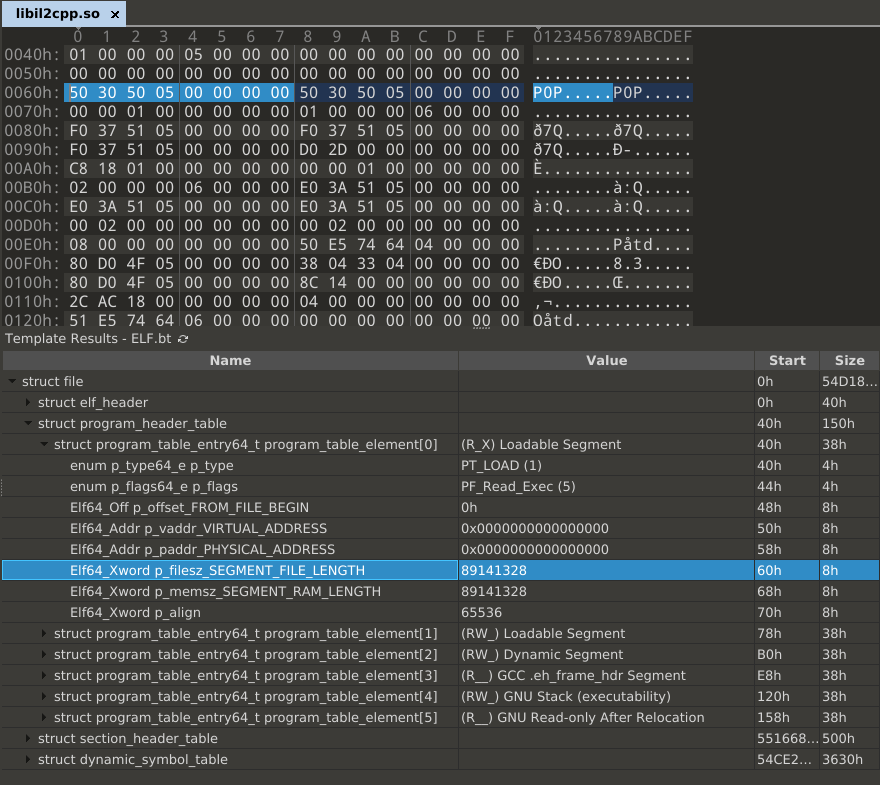

First of all we dont see a NOTE segment, this already indicated that the NOTE segment is either replaced with and extra RX segment. But there is none and neither is there an extra RW section which could store data. At least there is nothing which catches my eye.

Continuing with the sections there is something odd.

nth paddr size vaddr vsize perm name

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

...

6 0x054dab10 0x120 0x054dab10 0x120 -r-x .plt

7 0x016598ec 0x10 0x016598ec 0x10 -r-x .text

8 0x054fc9d0 0x6b0 0x054fc9d0 0x6b0 -r-- .rodata

...

The .text sections size is only 0x10, hmmm. Checking the content of the

section we can see that it only contains 16 bytes, and those are not even valid

instructions.

From our ELF understanding which we gained from my last post, we know that

executable code is usually stored in the .text section. But sections are for

linking and segments are used at runtime. So whats the size of the RX segment?

As we see 89141328 bytes will be loaded as RX, so the .text section is

simply a distraction. There is some data in this loaded data, but it does not

really seem to be any code (we will see in the next chapter).

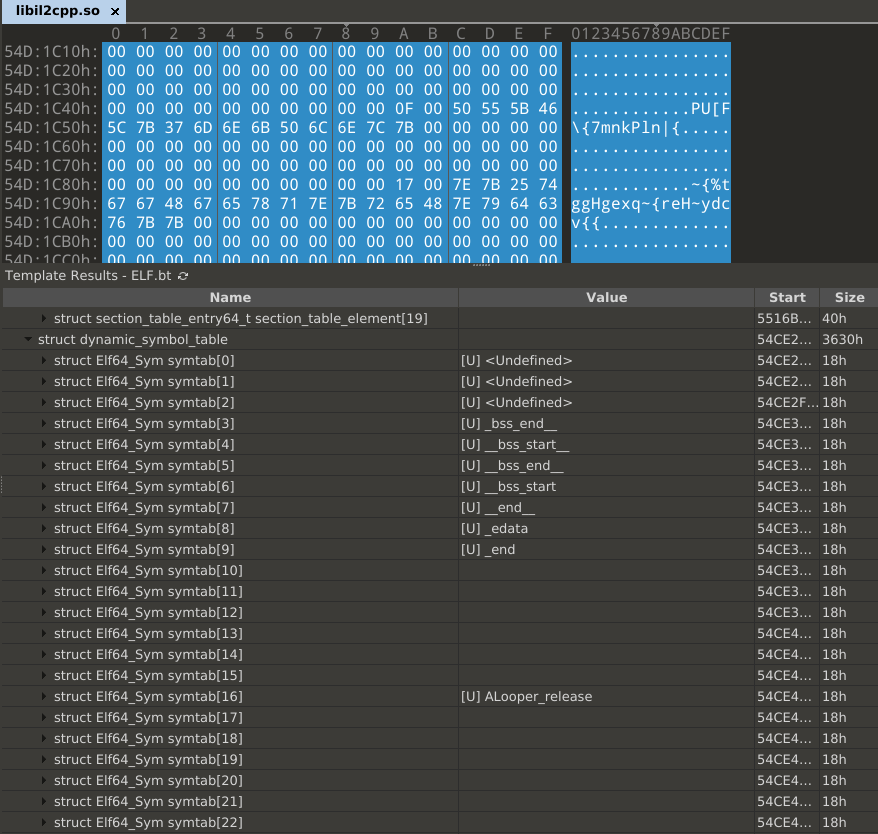

What else caught my eyes during inspection using 010editor, is the dynamic symbols. Those are used for example to store exports, which need to be found by the dynamic loader.

But in this case, some are completely removed as can be seen in the hexbytes and some are encrypted/encoded. The dynamic symbol table shows some entries those are probably needed right in the beginning the rest is empty. The encoded symbols are not shown in the table cause they start with a null byte.

IDA

After our first inspections, its time to start IDA and see whats the code

which gets executed first. Remember we still haven’t touched arkenstone.so or

the smali code. For the moment we are only interested in libil2cpp.so and how

the encryption might work.

It is anyhow a good advice if you try cheating in a game to gain as much information as possible during the static analysis phase. Once you run the game and attach a debugger or whatever you might get banned.

The first thing executed in a shared library are the functions from the

.init_array list. Those are called by the dynamic loader, if this is not

executable code. Than the library is decoded before its even loaded, meaning

probably from the Java side as libil2cpp.so is loaded very early. However

we find three functions, which contain executable code.

.init_array:00000073689D87F0 AREA .init_array, DATA, ALIGN=3

.init_array:00000073689D87F0 3C FC 99 68 73 00 00 00 sub_54DAC3C

.init_array:00000073689D87F8 68 FC 99 68 73 00 00 00 sub_54DAC68

.init_array:00000073689D8800 98 FC 99 68 73 00 00 00 sub_54DAC98

The function sub_54DAC98 looks pretty intersting, it looks like the decoding

code for the rest of the game library and furthermore its a super huge function.

It contains many calls via functions pointers, that seems to be a common thing

I see a lot of stuff like the following since a while:

func_ptrs[15] = (__int64)&sscanf;

func_ptrs[12] = (__int64)read_syscall_73689C191C;

func_ptrs[6] = (__int64)sub_73689B2A40;

func_ptrs[16] = (__int64)openat_wrapper_73689B2748;

func_ptrs[17] = (__int64)close_syscall_73689C1934;

func_ptrs[31] = (__int64)sub_73689B2A18;

func_ptrs[13] = (__int64)&lseek;

Including functions which implement their own syscall, as for example the read, close syscall shown above.

unsigned __int64 __fastcall read_syscall_73689C191C(int a1, void *a2, size_t a3)

{

int v3; // w19

_DWORD *v4; // x1

unsigned __int64 result; // x0

char v6; // cc

result = linux_eabi_syscall(__NR_read, a1, a2, a3);

v6 = (result != -4096LL) & __CFADD__(result, 4096LL);

if ( result > 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFF000LL )

result = ~result;

if ( v6 )

{

v3 = result;

v4 = (_DWORD *)__errno();

result = -1LL;

*v4 = v3;

}

return result;

}

Yea, stuff like that sucks for static analysis but once you debug, it doesnt matter. Implementing your own syscall makes sense to defend frida hooks, as the read implementation from libc is not called anymore.

SideNote: During analysis I found that the following code is calling what is supposed to be an anti-debug check, I guess:

if ( (*(unsigned __int8 (__fastcall **)(__int64 *))(*v3 + 72))(v3) )// anti-debug func

v182 = 0x55;

else

v182 = 0;

But analyzing the function I cant find where the return value is set, instead always zero is returned. To keep this post reasonable in size the code can be found here. As can be seen the pseudocode function will always return 0. Of course, I know, the pseudocode can be wrong but even during debugging when I changed the content of TracerPid it returned zero, so this “check” doesnt have any influence on the outcome.

TODO: write down string decryption function

grab the code

So we know now that the code is probably decoded by the third function of

.init_array. As we dont want to run the game attach a debugger or read

/proc/<pid>/mem cause both might be caught by the protection we use a

different approach. We write a wrapper application which is loading libil2cpp.so

on button click. This gives us a minimal app and time to attach IDA before we

press the button.

But dont forget we need to stop at the end of the decode function, in case we even get that far. There might be still other checks I did not caught yet. But as we can simply debug it we just have to step carefully through the code.

But yea we got lucky, it doesnt do a lot, besides xoring and writing bytes. Scary code like:

v8 = (unsigned __int8)(v8 + 1);

*v5 = (*(__int64 (__fastcall **)(_QWORD *, __int64, _QWORD))(*off_73689DC020 + 64LL))(off_73689DC020, v25, v11);

v5[1] = (*(__int64 (__fastcall **)(_QWORD *, _QWORD, _QWORD))(*off_73689DC020 + 64LL))(

off_73689DC020,

*(v5 - 31),

v12);

v5[2] = (*(__int64 (__fastcall **)(_QWORD *, _QWORD, _QWORD))(*off_73689DC020 + 64LL))(

off_73689DC020,

*(v5 - 30),

v13);

v5[3] = (*(__int64 (__fastcall **)(_QWORD *, _QWORD, _QWORD))(*off_73689DC020 + 64LL))(

off_73689DC020,

*(v5 - 29),

v14);

Turns out, that the function call simply does a xor, w0 = w1 ^ w2. At the

end of the decode function we can dump the content of the RX load segment and

then copy it into encoded library. I did this using an simple

IDApython script.

Once dumped to a file I simply wrote it into libil2cpp.so. Running strings

already shows a lot of il2cpp_ strings which indicates that everything seems

to be correct. Loading the new library into IDA also shows now 220 exports

instead of 4. Furthermore IDA finds now 28830 funcstions instead of 713.

Definitely and improvement.

We can now check for the function bytes of the previous get_mydamage_381EF7C

function. Over 1000 hits, uff, thats a lot. Going through some hits and thinking

about it. That acutally makes sense cause that function is a C# property and

those look the same for all C# properties. But at least we know that we are on

the right track.

next steps

We got the decoded code, in theory we could restore the library. Thats what we want cause we want the game without protection. However we are missing a view parts.

- For

libil2cpp.sowe dont know how what the original.init_arrayfunctions have been, we need to restore those too. - we still didnt look into the smali code

Smali Code

I always use JEB and grep here. Its now hard to reveil not the protection

due to so many plain strings…

On initialization the protection code checks for magisk using various methods.

static {

d.magisk_strings = new String[] {

"/cache/.disable_magisk", "/dev/magisk/img",

"/sbin/.magisk", "/cache/magisk.log",

"/data/adb/magisk", "/mnt/vendor/persist/magisk",

"/data/magisk.apk"

};

}

It also reads /proc/self/mounts and checks for the magisk string. So thats

easy to circumvent, dont use magisk or patch the strings.

The interesting part is what is happening after these checks. The protection uses a kind of heartbeat which is triggered on every touch event.

((View)v1).setOnTouchListener(new View.OnTouchListener() {

@Override // android.view.View$OnTouchListener

public boolean onTouch(View arg12, MotionEvent arg13) {

int v4 = arg4.getResources().getConfiguration().orientation;

long v0 = System.currentTimeMillis();

DisplayMetrics v12 = arg4.getResources().getDisplayMetrics();

arg3.a(arg4, String.valueOf(v0), arg13.getAction(), v4,

arg13.getToolType(0), v12.widthPixels,

v12.heightPixels, arg13.getX(),

arg13.getY());

return 0;

}

});

It collects various data which is then forwarded to a native function defined

in arkenstone.so. In there it will be probably send to some servers. We can

patch this by simply deleting the code in the onTouch function and leave it

empty.

Nothing more was found, it loads arkenstone.so and defines a couple of

native functions, which are all called in the same scheme inside the lib,

for example 0ooOo0O.... That makes it easy to break on all of them.

Putting it together

I patched the smali code and repackage it, and now its time for running the

complete game under a debugger. Cause I am interested what is still called

in arkenstone.so after patching the onTouch listener. To debug with IDA

right from the beginning I use a frida script which goes in an endless loop.

The endless loop is written in a CModule this way its easy with IDA to step

out of it. I dont wanna do the jdb startup trick as I am not interested in the

java part. The frida script can be found here.

Running it and debugging, gives me a crash in libmain.so, and taking a look

into it I can see that it has the same encryption than libil2cpp.so, interessting.

CONTINUE HERE

the arkenstone, heart of the mountain

Having now a good overview of what is happening, we can take a first look into

the heart of the mountain.

Interestingly this library does not have the same packer as libmain and

libil2cpp, this is intersting as it contains the security code.

Going through the .init_array functions we find a similar functions pointers

list as previously in .il2cpp, only way larger. Going through more functions

several self implemented syscalls can be found.

accessat, close, exit, getpid, gettimeofday, read, fstatat, uname, getdents64,

write, mprotect, pipe2, socketpair, openat, kill, recvfromm, sendto, geuid,

socket

Those are probably inplace to avoid simple frida hooks, using IDA debugger we can just set breakpoints on all of those and then inspect.

Moving on to plain strings in the library. The strings are not obfuscated this makes analysis very easy. There are a bunch of strings checking for root. Furthermore there are many emulator detection strings, intersting on those is that it checks for loaded kernel modules. There are also a bunch of other interesting strings which I could not really classify at first sight, if they are belonging to a check family or just for retrieving data about the device. For example whats the docker strings about? Googling gives me docker-android, I should give that a try looks really nice.

As a first idea, we can simply patch all the magisk strings (as thats the only thing I have installed on my phone) to madisk and then try running and debugging. I am not running on an emulator so I will leave those strings as is.

Approaching debugging with my IDA+frida combo, gives us already some nice outputs,

using frida I set hooks on basic libc functions like, open, opendir, openat, stat,

exit, dlopen, dlsym where I only print the file name in the hook to see whats

going on. Using IDA I do single stepping in and set breakpoints on interesting

stuff. As I changed the original apk due to the repack the open hook is

redirecting every access to the apk to with the real apk which is stored in

data/local/tmp. This looks as follows:

const open_libc = Module.findExportByName("libc.so", "open");

Interceptor.attach(open_libc, {

onEnter: function(args) {

var arg0 = args[0].readCString();

console.log("libc: open: " + arg0);

if (arg0 == "/data/app/com.live.of.turin/base.apk") {

args[0] == "/data/local/tmp/com.live.of.turin.apk"

console.log("--> /data/local/tmp/com.live.of.turin.apk");

}

}

});

Note: On my first run I didnt add this path replacement, and the game crashed pretty early, this shows that there is somewhere an integrity verification check inside the library.

During basic debugging we already get some interesting output from our frida hooks:

...

libc: stat: /system/lib/libc_malloc_debug_qemu.so-arm

libc: stat: /system/bin/droid4x-prop

libc: stat: /init.android_x86_64.rc

libc: stat: /system/lib/libldutils.so

libc: stat: /init.vbox86.rc

libc: stat: /data/./data/com.bluestacks.appmart

libc: stat: /system/./bin/nox-prop

...

It is definitely checking for a virtual environment. It calls the selfimplemented syscall: gettimeofday, uname, read. For easier tracking of those we add frida hooks to them.

What I noticed during debuging, the code scheme:

for ( i = 0LL; i != 24; ++i )

byte_addr1[i] = (~byte_addr2[i] - byte_addr1[i]) ^ byte_addr2[i];

is always decryption/decoding a string inplace.

The very weird thing is that the application seems to start a new process, cause my frida and debugging session dies, but the application continues to run and later crashes. But at this moment my debugger is long gone.

Furthermore it also seems not to fully end the app, it goes in background. Reactivating it from background continues the app, but I assume thats a restart cause it gets a new PID.

It dies definitely start some extra things, I dont know how thats working…

pme:/ # ps -A | grep u0_a95

u0_a95 2485 1298 4893120 482868 SyS_epoll_wait 7a91a0061c S com.life.of.turin

u0_a95 2866 2485 4553172 145552 hrtimer_nanosleep 7a91a01024 S com.life.of.turin

pme:/ # ps -A | grep u0_a95

u0_a95 2485 1298 4930664 404472 SyS_epoll_wait 7a91a0061c S com.life.of.turin

u0_a95 2866 2485 4553172 145552 hrtimer_nanosleep 7a91a01024 S com.life.of.turin

pme:/ # ps -A | grep u0_a95

u0_a95 2485 1298 4941488 421880 SyS_epoll_wait 7a91a0061c S com.life.of.turin

u0_a95 2866 2485 11812 1556 do_wait 7208b0675c S gameVoiceServ

u0_a95 3133 2866 8712 568 0 7208b06024 R gameVoiceServ

Open TODOs

I didnt wrote down everything yet, and I havent finished the full project, I will try to continue as soon as I will find time, open things are.

- restore original

.init_arrayfunctions - restore

libmain.so(same encoded as aslibil2cpp.so) - where is

global-metadata.datdecrypted

zu guter letzt ;)

If you have any question or like this kind of content dont hesitate to

reach out to me at niku.systems at gmail.com. Also let me know if you are

interested in my tools at http://niku.systems/#tools(still in slow develop)

or wanna hire me for a project.